Like many economists, I have been trapped into thinking that there is an equilibrium real rate of interest – a level of the policy rate consistent with stable inflation, a closed output gap, or full employment. The trick for policy makers is to find the magic level. From this perspective, the near-zero bound on monetary policy is only a problem if expected inflation is insufficiently high to set the real policy rate low enough to bring the economy back into equilibrium.

Increasingly, it has become clear that this entire framework is deeply flawed. For example, it is very likely that there is simply no level of the real policy rate in the Eurozone that will return the continent to trend growth. Why, after all, should the real interest be this all powerful lever which will single-handedly raise or shrink demand to the level consistent with stable growth and inflation?

The economic models which central banks operate with broadly assume that trend growth is a given – growth in labour supply and productivity are exogenous to the policy process. The two main sources of private sector demand are consumption and investment, both of which are also functions of real policy rates.

I have argued elsewhere that real private consumption spending is not a straightforward negative function of real interest rates. Theoretically for any given change in real interest rates there is an income and substitution effect, and there are good reasons to believe that the lower real interest rates go the less stimulus they have, and at very low real interest rates the sign may even change – lower real interest rates cause desired savings to rise. There are two basic reasons. Diminishing marginal utility of current consumption and the income effect dominating the substitution effect. To be clear, this is an empirical question, and there are good reasons to believe that in much if not all of the developed world at the moment lower real interest rates do not boost consumer spending.

Importantly, consumer theory doesn’t really deal with the non-trivial issue of which real interest rate consumers use to discount future consumption. This is an even more obvious challenge in thinking about investment functions. Even well-versed theoretical macroeconomists still talk as if investment spending is a straightforward function of the real policy rate. In a recent discussion on why private sector capex was so low, Robert Barro concluded that the expected return on investment must also be extremely low given that lacklustre private investment spending is coinciding with a negative real fed funds rate. He seems either oblivious to the fact that the cost of equity is not low, or deems the equity risk premium less relevant in determining private sector investment spending than the real fed funds rate – which seems decidedly odd.

Logically the real discount rate we think of as influencing private sector investment spending should be a cost of capital. All investment functions work off some variant of the principle that firms will invest up to the point where the marginal return on investment equals the marginal cost. But the real fed funds rate is not the firm’s marginal cost. Certainly a lower real cost of debt is part of this, but the equity cost of capital might be expected to dominate.

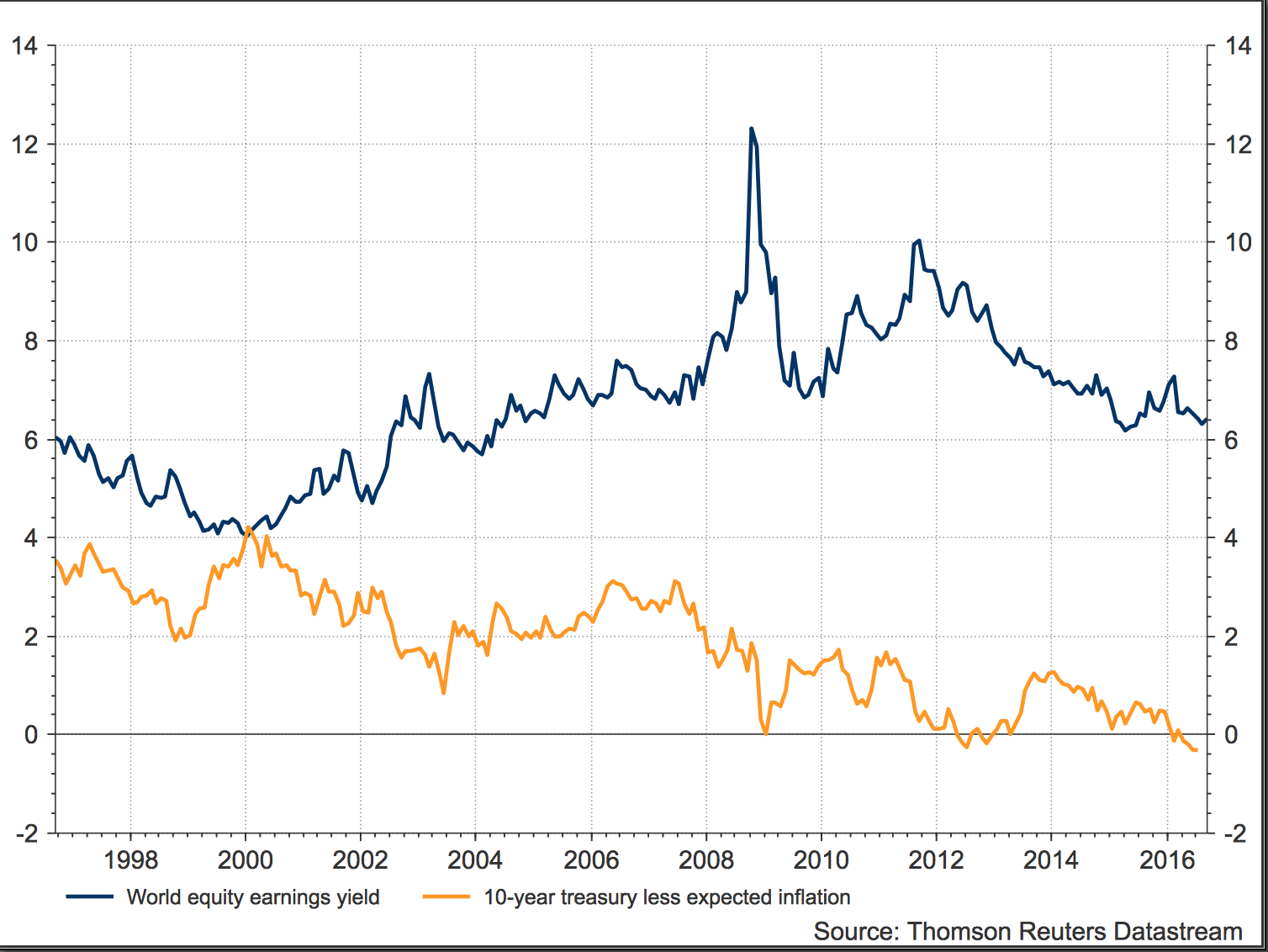

Think of it like this. What is interesting in the post-crisis phase is that the real earnings yield in most developed countries has barely moved, despite a collapse in real cash rates. A firm considering a new, risky, investment would not look to real cash rates to discount returns, but the real cost of equity – which is stuck at pre-crisis levels. Worse still, to the extent that we do not live in a pure modigliani-miller world, firms that can borrow without materially affecting their cost of equity would be wiser issuing debt and buying back shares, rather than engaging in uncertain productive returns. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that’s what many are doing.

It seems reasonable to argue that if the real cash rate moves independently of the real earnings yield (see chart) that it should have negligible impact on investment spending.

If the real policy rate at certain levels has negligible impact on consumption, or its effects cancel each other out, and simultaneously the real cost of equity appears immune to changes in the real policy rate, it is simply not the magical, all determining policy lever we would like it to be.

Let’s consider the Eurozone, where I think this is most likely true. I am very sceptical that ever lower real policy rates will raise consumption. Which is not to say that real rates should rise either – I think there is a level of real policy rates which do no harm. That level is probably somewhere near where we are. It is also very clear that low real interest rates, or lower real interest rates, are not particularly relevant to investment spending in the Eurozone – the equity risk premium is far too high, and is moving independently of cash rates.

Rather than denying the conceptual shift in thinking I am describing here, central banks should be open to it. If I am right, current policies of negative interest rates and government bond-buying are at best ineffective and at worst, damaging. It also focuses attention on alternatives. For example how can we reduce the equity risk premium?

My take on the weakness of private investment spending is of a textbook old Keynesian accelerator variety, as described recently by Brad DeLong. In straightforward terms, if aggregate demand (or final sales) could be raised, private investment spending would follow with increasing force.

Attachment to the belief that the policy rate is all-powerful also stems from a fear of the redundancy of monetary policy. This is erroneous. Monetary policy must simply be used to raise aggregate demand in other, more direct, ways.

Further reading

Income and substitution effects explained by Federal Reserve research staff

Income & substitution effects explained some more, with Euler equations and budget constraints.

The empirical evidence on the (lack of) effect of changes in r on investment

You can have too many doughnuts

What’s the equity risk premium? Intro by Damodaran